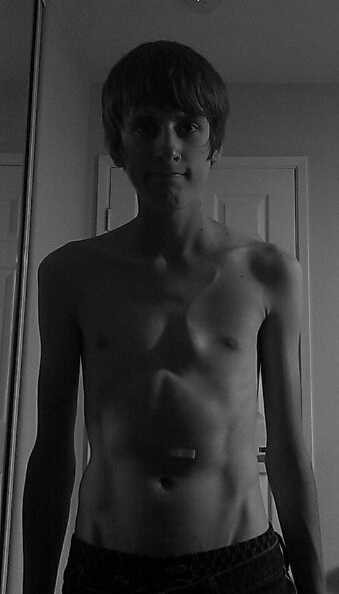

I’m taking a personal risk and posting some writing from a class I took on writing about chronic illness. I was told my weight is “perfect” (143 lb.) at my last doctor appointment. I don’t recall ever hearing that before. At the time that I wrote the essay (found below the photo), I was far below my target weight and shedding pounds every week. While my appetite isn’t amazing now, it has improved alongside my weight. Other than posting this as a celebration of my weight gain and how far I’ve come in my struggle, I want to make people aware of an aspect to cystic fibrosis that isn’t touched upon as much, thanks to lung issues overshadowing everything. Fellow cysters and fibros, do not lose hope. Better times can come.

Please keep in mind this was written in a different time in my life. Some things have been edited out for various reasons, so my apologies if there are inconsistencies. Also, I dedicate this to my buddy Poki, a cat like no other whose comfort made handling my disease a lot, lot easier.

‘Waste’

“Eat, please, please eat.” I put all of Poki’s favorite foods—ham, turkey, fish treats, yogurt—in front of his nose, one by one. His nose didn’t crinkle, his tongue didn’t whip out, his ears didn’t flick back and forth. He just stared unblinkingly at nothing, eyes dilated and sunk in. His purring had long since faded and he hadn’t mewed in hours. “Just eat. Please eat.” My leg tapped faster and faster, my mind filled with a buzzing noise, tears fell onto his orange fur, turning patches dark brown. His little ribs poked out, shifting with every labored breath. “How could you just give up on me, buddy? You know you have to eat.”

Eating is easy. In fact, it’s so easy that the desire to eat more than necessary is seen as normal, even addicting. At some point in the history of the human race, eating became less about survival and more about pleasure. Diets to lose weight are what take true effort. It’s the stick-thin models that make careers being featured in the pages of Vogue and Elle, not the overweight. The starving are the ones who worked hard. How many people would kill to eat whatever they want and not gain weight?

I wouldn’t kill for it. The very thing that gives me the ‘ability’ to eat and not gain is what’s killing me. Cystic fibrosis is classified as a lung disease, but the amount of effort it takes for a patient to breathe, their bodies’ inability to properly absorb fat, constant infections, and the nauseating, taste bud-morphing effects of antibiotics make it difficult (putting it lightly) to gain weight. “Malnourishment” and “failure to thrive” are words found on my medical records. I shove bite after bite of food into my mouth, pushing so hard to get extra calories, feeling like iron weights are dragging down on my jaw. I usually lose all progress, my tear-streaked face hovering over the toilet bowl, a lake of vomit. My appetite wasn’t always inexistent and I wasn’t always nauseated. Before, it came and went, came and went, came and went. I wrote food reviews for the campus paper for a couple years during the good-appetite-weeks. My last review was 15 months ago. Now, I only crave food about 30 minutes out of each week. I’ve run out of class and meetings when food is nowhere to be found and my stomach has chosen those 30 minutes in the week to feel desire. I’ve literally cried when the “30 minutes” are up microseconds before I’m about to bite into food.

I’ve worked so hard to boost my appetite and end my nausea. I’ve tried Zofran, ginger, Reglan, diet changes, Kytril, hypnosis, Megace, Periactin, lemon juice, Marinol, acupressure, Remeron, Prednisone. Some of them worked, but not without causing problems that forced me to stop them. Megace destroyed my body’s ability to make steroids, Prednisone made me angry and unable to sleep, Periactin and Kytril turned me into a zombie, Reglan gave me panic attacks. It has come to the point that my doctors seem to have given up on trying to boost my appetite and now focus on pumping fat into me through artificial means. I have my PEG tube to thank for that, a feeding port that sticks out of my stomach. Each night before bed, I pour five cans of 2Cal HN—which is kind of like Ensure but with an even more delicious sounding name—into a bag, then hook up the line from the bag into the PEG. 40 ounces of liquid fat drip into my stomach as I sleep. 2,375 calories, 107.5 grams of fat, and 99.5 grams of protein a night, yet I rarely gain a pound. I’m not supposed to taste it, but that’s unavoidable when I throw half of it up in the morning. It says “vanilla” on the can. Make no mistake, vanilla is the scent, not the taste. 2Cal HN is a concoction of bitter chemicals sprayed with really, really cheap vanilla perfume.

I didn’t cave into getting a PEG until 10th grade. It had always been a threat before then: “One more pound lost and it’s the PEG for you.” I feared nothing more than the PEG. It was just another step into being swallowed by the medical world. I had a better appetite then, so fighting was easier. I downed Ensure like shots of alcohol, tough to swallow, but handy for numbing my fears. I sometimes drank it while standing in front of a mirror with my shirt off, staring at my ribs to motivate myself. But the Ensure never left my house. I thought only old people and babies drink that stuff. So I focused on sugar when eating at school. My friends always laughed when I pulled out two Reese’s Fast Breaks and two Snicker’s from my pocket and ate them in a single sitting. Only God knows how I didn’t get cavities in those days, although being diagnosed with pre-diabetes a couple years later wasn’t too much of a shocker. It was, however, a shock that all my efforts ended only in me losing more weight and getting the PEG.

Recently, a doctor labeled my frustration with appetite loss as a “social concern.” As much as my friends care for me, my weight problem has always been a bit of a joke to them. I can’t count how many times I’ve heard someone say, “You can eat all you want and you don’t gain weight? I want that problem!” I can’t blame them. I even share an awkward laugh with them. Many of them don’t know what it feels like to be so weak and nutrient-deprived they can’t get out of bed or have what was once delicious taste like dust. I think many people don’t realize how deeply rooted social enjoyment is in food. Not every dining experience is an obligation rather than a pleasure for them. They don’t know the shame I feel when they make remarks about how much food I waste when we go out to eat, despite them being the ones who beg me to order something so they don’t have to eat alone. They haven’t put thought into what the best technique is to make a plate of food appear as if it has been enjoyed. (Cut the food into pieces and shift it around, exposing as much of the white plate beneath as possible. Keep your dining partner engaged in conversation so they stare at your mouth and eyes rather than your plate. Ask them if they want to try some of the food and hope they do. Make sure to comment on how tasty the food was before asking for a leftovers box, which will sit in the fridge untouched for days after.)

Sometimes, I can’t remember how much I eat. Entire days go by without me realizing that I haven’t had a meal or even a snack. My stomach rumbles during class and I wonder if it’s a side effect from my medicines. My friends remark at 6 p.m. they haven’t eaten since breakfast and I’ll try to add up the days since I’d even had a snack. My doctors have me fill out these logs of how much food I’ve had the past three days. Two Oreos, half a slice of toast, a handful of gummy bears. Thank God there are so many calories in juice and soda. Between the drinks and 2Cal HN, the sums of calories tallied up at the bottom of the log don’t look that bad. But it wasn’t good enough for one doctor years ago.

The doctor slammed the door and locked it. I’d never met him before then. Another doctor had recommended I talk to him about ideas to increase my weight. He interrogated me about my eating habits, asked if I “even try” and said he always eats if he’s sick because he knows it’s what he has to do. Strong, tall, he towered over me. “Do you know who else stopped eating? My grandma. Before she died.” I took his yelling for what seemed like hours before I demanded that he leave the room, then told the other doctors I never wanted to see him again. He had pushed my buttons. Was I even trying? In hindsight, of course I was. But the thing about having a chronic disease is that “victims” often blame themselves for their own sickness—the disease, after all, is in and of our own body. Hours are spent wondering how much healthier I could be if I had just taken those extra bites, if I had just gotten dessert instead of a salad, if I had just spent that extra dollar to have bacon added, if I had just “ .”

Shelby’s hand’s maneuvered between boxes of rotting leftovers in the fridge that I’d never gotten around to finishing, grabbing ingredients to make one of my favorites: steak fajitas. I salivated at the smell of my sister’s cooking. It was tempting enough to make me join my family at the dinner table, leaving Poki’s side for the first time in hours. We prayed over the dinner, one of my eyes open and staring at Poki in the other room. The smell of the food was now so intense that I lifted my clasped hands to cover my nose until the prayer was over. My stomach was bubbling, appetite plummeting. My parents and sister dug in, scooping generous servings of steak, peppers, and onion onto tortillas. I couldn’t even touch the serving spoon. “I made this just for you,” I heard Shelby say somewhere amidst the buzzing in my ears. I couldn’t stop staring at Poki and thinking of ways to make him eat.

2 Comments